Published on June 11, 2021 by Mahesh Agrawal

“Our task is not to bring order out of chaos, but to get work done in the midst of chaos” – George Peabody. And it was perfect chaos at the start of 2020 when COVID-19 hit without warning. Pessimism was at its peak, with global equity markets losing 20-25% of market capitalisation within a short period of time. Central banks, governments and financial institutions across the world reacted fast and at scale to help their respecive economies and financial markets recover quickly. After nearly a year, the globalfinancial market appears to be healthy, with riskier assets including equities and commodities (especially metals and agriculture) making new highs. The energy sector is still some distance away from pre-crisis levels; but as vaccination programmess pick up pace and travel resumes, we could also see energy demand moving back to normal levels probably by next year.

Against this backdrop, the debate has started to shift to how long excessive supportive policies need to be continued before they create long-term economic imbalances. Supporters of easy monetary policies argue that the actual economic environment remains quite fragile with the pandemic yet to be fully controlled. The recent second wave of infections in Asia and the limited availability of vaccines, in addition to their unproven efficacy against many variants of the virus, weigh on economic reopening; policy support is perceived to be necessary to maintain systemic stability. On the other hand, excessive leveraging is blamed for the inflated asset prices that have been increasing systemic risk for the market. As Hyman Minsky aptly summarises, “the more stable things become and the longer things are stable, the more unstable they will be when crisis hits”. As inflation creeps up and fixed-income products fail to match the rising cost of living, riskier bets have been piling up to make up the difference; this could increase the probability of a blow-up when deleveraging starts.

US – stimulus-fuelled recovery

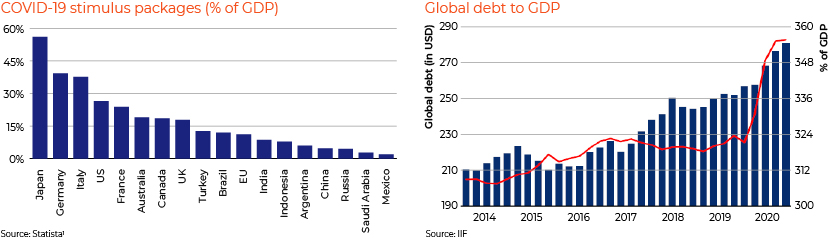

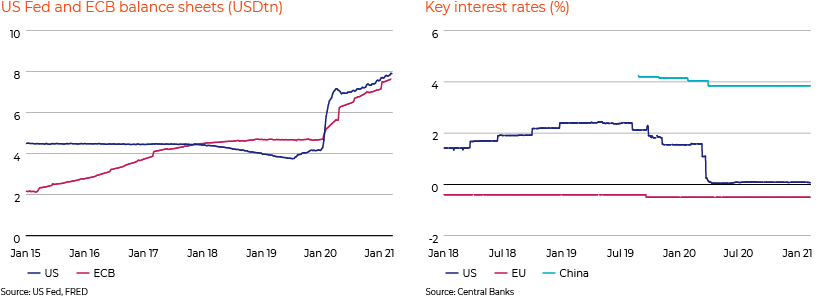

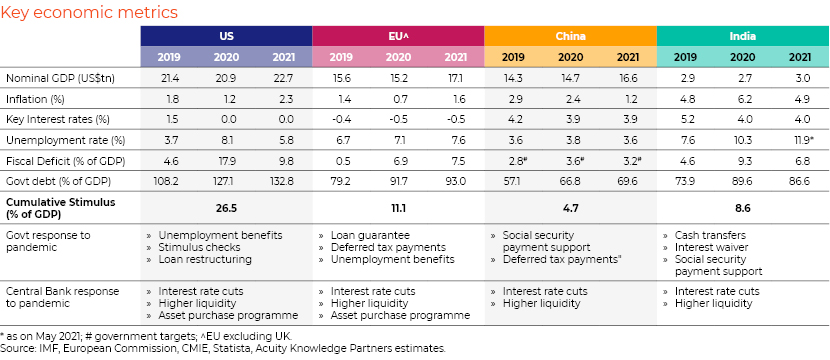

The US has been one of the most active countries in terms of providing policy and fiscal support in response to the COVID-19 crisis. The US Fed has lowered its interest rates to near zero since early 2020 and expanded its balance sheet from USD4.2tn at the end of 2020 to USD7.9tn as of 24 May 20211 (88% expansion) to support corporate financing requirements. The US Congress has also provided more than USD5tn in economic stimulus3 to date since early 2020 (including USD2.2tn under the CARES Act in March 2020, a USD0.9tn relief package in December 2020 and the USD1.9tn American Rescue Plan in March 2021), making up roughly 26.5% of US GDP4 .

The support measures were mainly aimed at supporting the US working class, which the pandemic hit the hardest, with unemployment surging to 14.8% in April 2020 (it remained elevated at 6.1% in April 2021, compared to pre-pandemic levels of around 3.5%). The US Fed expects the unemployment rate to fall to 4.5% by end-2021, 3.9% in 2022 and 3.5% in 20235 . The Fed’s dual mandate requires that it work towards maximum employment in addition to maintaining price stability, which means a rate hike seems unlikely at least until mid-2022.

On the other hand, higher spending has been slowly translating into inflation; it reachd 4.2% in April 2021, compared to 2.6% in March 2021 and much higher than the Fed’s target of around 2%. Market expectations over the medium term are also quite high, with derived breakeven inflation from five-year Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) increasing to a decade-high 2.7% in May 20216 . The Fed has been somewhat dismissive of inflation fears, calling them transitory; however, they could be difficult to ignore if inflation remains elevated. Higher inflation points to an overheating economy and may put pressure on the Fed to take corrective measures.

Europe – the worst may be over but uncertainty remains

“Extraordinary times require extraordinary action. There are no limits to our commitment to the euro” –ECB President Christine Lagarde. Interest rates in the EU were below zero even before the pandemic and have remained at ultra-low levels amid it to help money flow into the economy. Besides maintaining ultra-low interest rates, the ECB has been supporting the financial markets by measures such as providing additional liquidity to banks, a EUR1.85tn Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) and flexible accounting rules and regulatory requirements. Total COVID-19-related stimulus in the EU is estimated at around 11% of regional GDP to date; this is significant considering the support of 9-10% of GDP during the financial crisis of 2008-09.

Europe’s GDP contracted by around 6.1% in 2020 as private consumption nosedived and the unemployment rate surged. In its spring 2021 forecasts7 , the European Commission estimated that GDP could recover by around 4.2% and 4.4% in 2021 and 2022, respectively, as private consumption picks up and real GDP likely matches pre-crisis levels by about 2Q 2022. The Commission reports that the unemployment rate in the EU increased from around 6.7% in 2019 to 7.1% in 2020 and 7.6% in 2021; it expects it to fall to 7.0% by 2023, still higher than levels seen in 2019. These estimates are based on the assumption that containment measures are relaxed significantly from 2Q 2021 and the crisis is resolved by early 2022. The unpredictable nature of the crisis and the second wave of infections in Asia have increased downside risks to these forecasts.

We believe the economic situation in the EU is more fragile given slower economic growth and high public debt in some of the countries, the slowdown in investment and uncertainty surrounding Brexit. Monetary and policy stimulus, largely in force for more than one decade, has helped the Eurozone avoid a bigger crisis, although the economy is not out of the woods yet. As such, options for the ECB to cut back on policy supports are limited, as the risks of premature withdrawal could outweigh the benefits.

Source: IMF, European Commission, CMIE, Statista, Acuity Knowledge Partners estimates

China – focus on deleveraging

China has been more prudent in its policy support amid the crisis, providing fiscal stimulus only of around 4.7% of GDP. The country has handled the COVID-19 crisis surprisingly well and economic activity resumed in April 2020, reducing the need for large-scale government support. Besides fiscal support, China has also taken monetary policy measures, including reducing the lending rate to 3.85%from 4.15% at the start of 2020 and boosting liquidity in the system, but these measures are far more limited than those taken by Europe and the US.

That said, China was expanding its balance sheet quite strongly even before the pandemic to meet its high GDP growth targets. China’s debt-to-GDP ratio hit a high of 335%8 at end-3Q20 compared to around 300% a year ago and around 240% at the end of 2015, reflecting high leverage for the banking sector. At the recently concluded annual meeting of the National People’s Congress, China recognised the financial risks associated with high debt and emphasised the need to keep debt levels in check. The country targets modest GDP growth of 6% for 2021 against market consensus of c.8%, indicating Beijing’s cautious approach to economic recovery. Sustainable growth over the long term appears to be the administration’s central message, rather than debt-fuelled short-term growth that could jeopardise economic and financial stability in the long term. China aims to narrow its fiscal deficit to 3.2% of GDP in 2021 (compared with last year’s target of 3.6%) to keep debt levels in check.

Deleveraging may not come easy even for China, as the external sector remains a big contributor to economic activity in the country. Also, export demand remains at risk owing to multiple factors, including the global economic slowdown due to the pandemic, the debate on the origin of the coronavirus, trade and currency controls and uncertainty around the US-China trade deal. In addition, deleveraging could result in bond defaults and business closures in the country; while Beijing may tolerate these to an extent to clean up the system, it may not risk disrupting the whole system when COVID-19-related risks are still not fully resolved. Chinese corporate bond defaults were up 14% y/y to around USD30bn in 20209 , and we believe the government may have to provide policy support if defaults exceed USD35-40bn this year.

India – second wave of infections slows the recovery

India was well on the path to recovery before the second wave hit, leading to more lockdowns and other restrictions for most of the country. Although it avoided a national lockdown this time around, local lockdowns and restrictions resulted in the unemployment rate rising again to around 10%, last seen in 2Q20.

India’s financial response to the crisis was similar to that of other economies; it has reduced the interest rate to 4% from 5.15% at the start of 2020, and the government has announced liquidity and financial support for distressed sectors. The crisis saw the fiscal deficit widening to 9.3% of GDP in FY21; this is likely to narrow to around 4.5% only by FY26, although still higher than pre-crisis levels.

Higher FDI inflow, lower crude oil prices and increasing demand for IT-related services have helped keep India’s external balances strong even amid the crisis. A comfortable supply of foreign currency has also helped the central bank keep monetary policy loose. However, with a debt rating just above “junk” status and a wide fiscal deficit, we believe options for further policy or fiscal support remain limited. Also, India has been struggling to keep inflation in check since the crisis began due to supply constraints and easy monetary policy. Wholesale inflation surged to a record high 10.5% in April 2021; retail inflation has also been quite high since the start of 2020. With the Reserve Bank of India targeting retail inflation of 2-6% over the longer term, high inflation, if unchecked, could pressure it to tighten monetary policy sooner than the market expects.

Conclusion

Central banks acted decisively when the crisis hit early last year, and the need for their support remains. In fact, withdrawing policy support prematurely risks an economic meltdown. Economic metrics such as debt-to-GDP ratios and inflation remaining above official targets are a cause for concern, but we believe these could be tolerated for the time being, at least until the pandemic is perceived to be largely under control.

How Acuity Knowledge Partners can help

Acuity Knowledge Partners (Acuity) provides expertise for market research on industries, economies and commodities. Our team has a firm grasp of macroeconomic and market concepts, and expertise in technical and quantitative analysis to provide in-depth market insights on relevant topics. We help clients manage increasing demand on their teams by providing customised managed-services solutions, based on specialised skills and technology, and by delivering operational efficiency, resilience and significant cost savings.

1https://www.statista.com/statistics/1107572/covid-19-value-g20-stimulus-packages-share-gdp/

2https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/bst_recenttrends.htm

3https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/03/10/coronavirus-stimulus-international-comparison/

4https://www.statista.com/statistics/1107572/covid-19-value-g20-stimulus-packages-share-gdp/

5https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomcprojtabl20210317.htm

6https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/T5YIE

7https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/economy-finance/ip149_en.pdf

8https://www.reuters.com/article/us-global-debt-idUSKBN27Y239

Tags:

What's your view?

About the Author

Mahesh has over 14 years of experience in commodity and macroeconomic research and has been associated with Acuity Knowledge Partners (Acuity) since September 2012. At Acuity, he supports a leading European investment bank’s commodity research desk in analysing commodity markets, preparing research notes and creating presentations for conferences and client interactions. Mahesh holds a master’s degree in Science (Energy Trading) from the University of Petroleum and Energy Studies, Gurugram, and a Bachelor of Science from Bikaner University, Bikaner.

Like the way we think?

Next time we post something new, we'll send it to your inbox